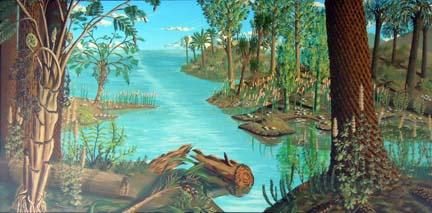

Carboniferous Tropical Forest

Treena Joi*

A large seed fern is in the left foreground, with a giant horsetail trunk on the ground behind. On the right and going back are giant club moss Scale trees. On the shore behind are giant scouring rushes, a grove of Cordaites (conifer-like trees) and a group of tree ferns. Smaller plants are various horsetail rushes. (*original painting on display at Cal Poly Humboldt Sci C 2nd floor—botany hall)

318.1 to 299.0 Million years ago

Richard Paselk

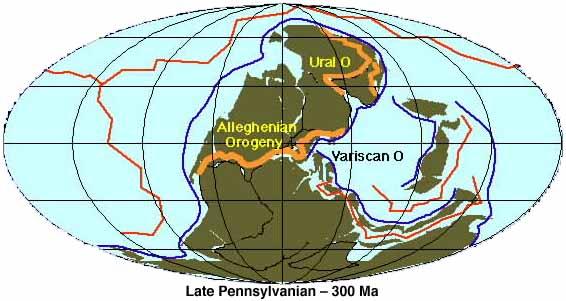

Plate Tectonic Reconstructions

These maps of major tectonic elements (plates, oceans, ridges, subduction zones, mountain belts) are used with permission from Dr. Ron Blakey at Northern Arizona University. The positions of mid-ocean ridges before 200 Ma are speculative. Explanation of map symbols.

The Pennsylvanian* saw the disappearance of the warm, shallow seas of the Mississippian, causing a dramatic change in marine life. The warm, clear seas of the Mississippian gave way to cool, muddy waters resulting in a decline in crinoids from which they never recovered. On land coal swamp forests thrived during this period. The dead plant material was laid down in huge amounts, gradually forming today's coal. Insects ruled the air.

Tropical forests of this Period provided the plant matter that later became the great coal deposits of America and Europe. These rich deposits make these forest plants some of the best known in Earth’s history. Dominant plants included giant club mosses and horsetails, tree ferns, seed ferns and cordaites (conifer-like trees). Specimens of all but cordaites are displayed in this case. Late Pennsylvanian temperate forests were dominated by cordaites. The vast amont of carbon deposited as coal, rather than carbonate (CO32-), released oxygen into the atmosphere, increasing atmospheric oxygen to 35% (vs. 21% today). This allowed the evolution of giant invertebrates, for example, dragonflies with 70 cm (29 in) wingspans and two-meter long millipedes.

Pennsylvanian forests and swamps were home to a rich diversity of animals, particularly winged insects. Insects and other arthropods were the main herbivores (vertebrates had not yet evolved the complex digestive strategies needed to eat plants). This Period is known as the Age of Amphibians due to their numbers and variety. These animals ate insects, other arthropods, and each other. A crucial development of this Period was the evolution of the land adapted, membrane enclosed (amniote) egg, allowing animals to live away from water. This advance enabled the eventual conquest of land by reptiles, mammals, and birds.

Significant glaciation marks the beginning of the Pennsylvanian with a resultant sea-level drop. Earth was in an ice age with a climate much like today—ice on both poles with wet tropics near the equator and temperate regions between. While the main mass of continents was connected, fragments on the edges of the plates continued colliding and merging during this Period, continuing the process of the formation of the supercontinent of Pangea (a process to be completed by the early Triassic). This was also a time of mountain building as all of the continents came together. With mountains came erosion and silt, resulting in muddy shallow waters. As the continents moved about, corresponding climate changes occurred. Towards the end of this period many swamps dried out, leading to the demise of giant plants.

*The Pennsylvanian was named for the coal-bearing beds in Pennsylvania by J.J. Stevenson in 1888.

Pennsylvanian Animal (Metazoan) Fossils

Trilobites (ToL: Trilobites<Arthropoda<Ecdysozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Trilobites

Trilobites are represented by a single specimen:

Echinoderms (ToL: Echinodermata<Deuterostomia<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Sea Stars

Free living echinoderms are represented by the Asterozoan, a starfish (sea star = Asteroidea) resting place:

Crinoids

Although declining, sea lilies or crinoids (Crinoidea) are still found, as represented by Erisocrinus typus (white) and Stellarocrinus bilineatus. A large crinoid stem fossil is also shown.

Sea cucumbers

Sea cucumbers (holothuroidea) are soft bodied echinoderms, and thus rarely fossilized. The fossil remains of Achistrum sp., in positive and negative impressions are therefore very special.

![]() positive impression

positive impression ![]() negative impression

negative impression

Mollusks (ToL: Mollusca<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Gastropods

Gastropods flourished in the Pennsylvanian. Two specimens of Worthenia sp. are displayed.

Bivalves

Mobile bivalves flourished on the muddy sea floors, displacing the sedentary brachiopods. A clump of fossilized mussels, Myalina perattenuata, are displayed.

Brachiopods (ToL: Brachiopoda<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Brachiopods

Brachiopods were smothered on muddy bottoms, the spirifereds declined. Two brachiopod species are displayed: Dictyoclostus sp. and Linoproductus sp.

Tully Monster (ToL: ??<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

The Tully monster, Tullimonstrum gregarium, is an unusual animal of unknown taxonomic affiliation – it is not even known what phyla it belongs to. Some have compared it to the unusual soft-bodied fossils of the Cambrian, like them it is part of an unusually well preserved ecosystem, in this case the Mazon Creek fossils of Illinois, including soft-bodied animals, many with unknown or uncertain modern decendents.* Thus far these animals have not been found anywhere else in the World. The Tully monster was probably an active, swimming predator – it had up to eight small teeth in each "jaw" of its proboscus.

Fossil, proboscus missing,

Fossil, proboscus missing,  Fossil head, note cross-bar with "eye" knobs on either side.

Fossil head, note cross-bar with "eye" knobs on either side.

artist interpretation from fossil cast

artist interpretation from fossil cast

* "The formation of the Mazon Creek fossils is unusual. When the creatures died, they were rapidly buried in silty outwash. The bacteria that began to decompose the plant and animal remains in the mud produced carbon dioxide in the sediments around the remains. The carbon dioxide combined with iron from the groundwater around the remains, forming encrusting nodules of siderite ('ironstone'), which created a hard permanent 'cast' of the animal which slowed further decay, leaving a carbon film on the cast. The combination of rapid burial and rapid formation of siderite resulted in excellent preservation of the many animals and plants that ended up in the mud. As a result, the Mazon Creek fossils are one of the world's major Lagerstätten, or concentrated fossil assemblages." from Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tullimonstrum (downloaded 11/03/2014)

Corals (ToL: Cnidera<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Cnidarians

Cnidarians (corals): Both small (Lophophyllum profundum) and large (Caninia torquia) horn corals are in the collection.

Pennsylvanian Plant Fossils

Vascular Plants (ToL: Embryophytes [land plants] <Green Plants<Eukaryota)

Ferns

Filocopsida (ferns and their relatives) were common in the coal swamps of this period. Fern leaves, such as those of Alethopteris seilii, looked much as they do today. Tree ferns (represented by a Pecopteris sp. leaf) grew to 50 ft.

Seed ferns

Seed ferns had leaves similar to the true ferns, but differed in having pollinated seeds. They thus avoided the separate sexual plants and the dependence on standing water for reproduction. They may have been the ancestors of the flowering plants. Fossils in this case include: a single leaf and and a cluster of leaves of Neuropteris sp., and a leaf from Sphenopteris artemisaefolioides (positive and negative impressions).

Sphenopteris artemisaefolioides

![]() positive impression

positive impression ![]() negative impression

negative impression

Rushs

Equisetophyta (Sphenophyta, rushs), similar to todays horsetail rushes, but often much larger (up to 30 feet tall), were both diverse and common. A number of species of Scouring rushes are represented: Annularia longifolia (positive and negative impressions), Annularia stellata, and a scouring rush trunk (Calamites sp.). There is also a Sphenophyllum emarginatum (positive and negative impressions).

Annularia longifolia

positive impression

positive impression  negative impression

negative impression

Calamites sp.

Calamites sp.![]() life reconstruction from A Text-Book of Geology

life reconstruction from A Text-Book of Geology

Sphenophyllum emarginatum

![]() positive impression

positive impression ![]() negative impression

negative impression

Lycopods

Lycopodiophyta or Lycopods (primitive trees) were among the earliest trees, reaching heights of up to 100'. The scale tree or giant club moss (Lepidodendron) specimen shows the surface patterns characteristic of the bark of these organisms.

![]() Lepidodendron

Lepidodendron ![]() life reconstruction with details of leaf and bark from A Text-Book of Geology

life reconstruction with details of leaf and bark from A Text-Book of Geology

The engravings are from Dana, James D. (1870) Manual of Geology, Le Conte, Joseph (1898) A Compend of Geology, Louis Pirson and Charles Schuchert, A Text-Book of Geology. (1920), or McMurrich (1894) Invertebrate Morphology.

©1998, Cal Poly Humboldt NHM | Last modified 5 November 2014

Ditomopyge scilius

Ditomopyge scilius Asterozoan

Asterozoan Erisocrinus typus

Erisocrinus typus crinoid stem

crinoid stem Myalina perattenuata

Myalina perattenuata Linoproductus sp

Linoproductus sp Alethopteris seilii

Alethopteris seilii Neuropteris sp.

Neuropteris sp. Annularia stellata

Annularia stellata