Mississippian Crinoid Meadow

Sarah Hamblin

Long-stemmed, colorful, flower-like crinoids and their blastoid (yellow) relatives dominate the scene. In the foreground a sea star is nestled between some horn corals, bryozoan colonies grow among the green algae (seaweeds), and a couple of brachiopods lay on the sandy bottom.

359.2 to 318.1 Million years ago

Richard Paselk

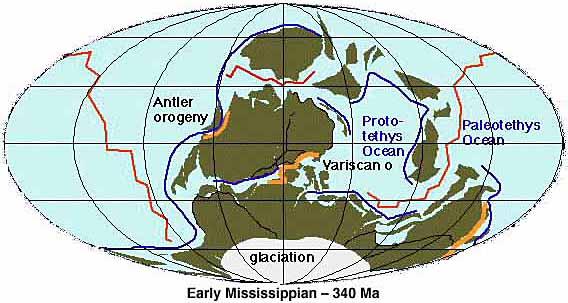

These maps of major tectonic elements (plates, oceans, ridges, subduction zones, mountain belts) are used with permission from Dr. Ron Blakey at Northern Arizona University. The positions of mid-ocean ridges before 200 Ma are speculative. Explanation of map symbols

During the Mississippian* sea lilies dominated the seas and reptiles began to appear on land, along with ferns. Shallow, warm seas supported dense meadows of crinoids and blastoids along with corals, arthropods and mollusks. In North America these meadows left marine limestone deposits, which distinguished the Mississippian from the later coal-rich, Pennsylvanian. Crinoids and their relatives, blastoids, were so widespread in North America that the Mississippian is known as the Age of Crinoids. Because crinoids are filter feeders the seas must have been relatively clear, while their need for high calcium carbonate (CaCO3) concentrations to build their skeletons points to a warm water environment. Bryozoans and brachiopods also thrived in these shallow seas, but trilobites continued to decline. Ammonoids grazed in and on the meadows of less mobile animals. Among the fishes sharks were especially common while bony fishes included coelacanths, acanthodians, and lungfishes. The common open communications between the continental shelves of this Period resulted in a marine fauna which was generally distributed Worldwide.

In the early Mississippian, diverse scrawny treeless forests replaced the Devonian forests dominated by a single species of tree (Archeopteris). An increasingly lush flora evolved as the period progressed, common plants soon included giant horsetails, tree ferns and conifer-like trees (cordaites). The new flora provided ample food for arthropod herbivores and detrivores such as millipedes and the newly evolved winged insects. These arthropods were in turn food for arthropod and vertebrate predators. Amphibians diversified to include many forms of both semi-aquatic and fully terrestrial species, which fed on the rich arthropod fauna and/or each other.

Both the Mississippian and the Pennsylvanian are now considered to be subperiods of the Carboniferous Period. They are separated in the U.S. because of the different types of fossil deposits commonly found for each subperiod, where much of the midwest was covered by shallow seas giving limestone in the Mississippian, while the Pennsylvanian is dominated by coal deposits from widespread swamps. A major marine extinction event, caused by a drop in sea level that hit ammonoids and crinoids especially hard, distinguishes the Mississippian from the Pennsylvanian periods in marine deposits.

Although the Devonian ended with a series of glaciations and extinction events, the early Mississippian saw the Earth in a greenhouse climate state with warm temperatures over much of the globe. Gondwana continued its northward drift and collision with Euramerica, building the Appalachian Mountains. Because the colliding landmass straddled the equator warm climatic conditions were common over a wide range of its northern latitudes while southern Gondwana remained glaciated. The drop in sea levels at the end of the Devonian was soon reversed in the Mississippian. The widespread shallow seas on the continents resulted in the extensive limestone and dolomite deposits in this Period, the last Period to see limestone (the major Mississippian rock type) deposited by widespread seas on the North American continent..

*The Mississippian was named for rocks in the upper Mississippi Valley by Winchell in 1870.

Mississippian Animal (Metazoan) Fossils

Trilobites (ToL: Trilobites<Arthropoda<Ecdysozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Trilobites had suffered significant extinctions at the end of the Devonian, suffering over a 50% loss of families. There is a single Mississippian trilobite, Griffithides bufo, displayed.

Echinoderms (ToL: Echinodermata<Deuterostomia<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Crinoids

As befits the Age of Crinoids (Crinoidea) a wide range of fossil crinoids (particularly the stemmed forms, or sea lilies) are displayed:

Dichocrinus striatus and Cryptoblastus melo,

Dichocrinus striatus and Cryptoblastus melo,

Aorocrinus immaturus and Platycrinites symmetricus,

Aorocrinus immaturus and Platycrinites symmetricus,

Taxocrinus colletti, Barycrinus princeps,

Taxocrinus colletti, Barycrinus princeps,

Sea Lily, Barycrinus sp.

Sea Lily, Barycrinus sp.

![]() Sea Lily, Scytalocrinus sp.

Sea Lily, Scytalocrinus sp.

A more common fossil than the body of the sea lilies are pieces of their stems. Here we see a collection of crinoid stems, an assemblage of crinoid stems, and a slab with crinoid stems.

![]() collection of crinoid stems all showing branch attachment site.

collection of crinoid stems all showing branch attachment site.

![]() assemblage of crinoid stems

assemblage of crinoid stems

slab with crinoid stems

slab with crinoid stems

Blastoids

The related blastoids (Blastoidea), common during this Period, are also well represented:

Mollusks (ToL: Mollusca<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Gastropods

Gastropods (Gastropoda) are represented by a single snail,

Cephalopods

Cephalopods: Ammonoids lost almost all of their families in the Devonian extinction. Muensteroceras parallelum represents the survivors in this display.

Brachiopods (ToL: Brachiopoda<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Brachiopods

Brachiopods suffered important losses in the Devonian extinction, but many families survived into the Mississippian. A single species is represented by a pair of small specimens in this case.

pair of specimens of Composita sp.

pair of specimens of Composita sp.

Corals (ToL: Cnidera<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Cnidarians

Cnidarians (corals): Less than half of the coral families survived into the Mississippian. Specimens of both a solitary horn coral and a colonial form of rugose coral, Lithostrotion proliferum, are shown.

The engravings are from Dana, James D. (1870) Manual of Geology and Le Conte, Joseph (1898) A Compend of Geology.

Last modified 10 August 2012| ©1998, Cal Poly Humboldt NHM

Griffithides bufo

Griffithides bufo Abatocrinus sp.

Abatocrinus sp. Barycrinus asteriscus

Barycrinus asteriscus Pentremites godoni major

Pentremites godoni major Pentremites pyriformis

Pentremites pyriformis

Muensteroceras parallelum

Muensteroceras parallelum horn coral

horn coral Lithostrotion proliferum

Lithostrotion proliferum