Devonian Transition

© G. Paselk

During the Devonian a few freshwater fish began the transition to life on land. Here we see two different tetrapod protoamphibians, one Acanthostega and two Icthyostega in a pool along with three lungfish (Dipterus) and a placoderm (Bothriolepis). Primitive land plants, including the early trees Archeaosigillaria and Archaeopteris, are shown on the shore in the background.

408,000,000 to 360,000,000 years ago

Richard Paselk

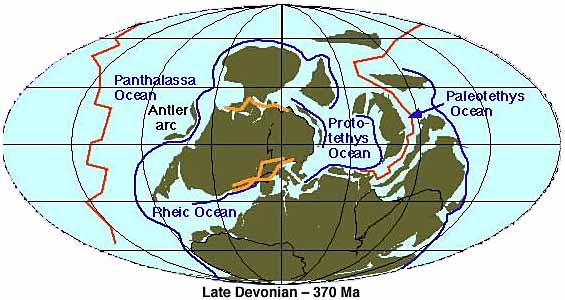

Plate Tectonic Reconstructions

These maps of major tectonic elements (plates, oceans, ridges, subduction zones, mountain belts) are used with permission from Dr. Ron Blakey at Northern Arizona University. The positions of mid-ocean ridges before 200 Ma are speculative. Explanation of map symbols

The Devonian* saw the peak of marine faunal diversity during the Paleozoic Era. New predators such as sharks, bony fishes and ammonoids ruled the oceans. Trilobites continued their decline, while brachiopods became the most abundant marine organism. A wonderful assemblage in the collection has fragments of trilobite (Phacops rana milleri), brachiopod (Sulcoretepora deissi) and bryozoan fossils, all replaced with pyrite. Oceanic conditions and biological richness resulted in the greatest production of carbonate during the Paleozoic Era.

The Devonian saw major evolutionary advancements by fishes with diversification and dominance in both marine and fresh water environments—the Devonian is also known as the “Age of Fishes.” Jawless fish and placoderms (such as the giant 33 ft Duncleosteus) reach peak diversity and sharks, lobe-finned, and ray-finned fishes first appear in the fossil records. Finally, the changing land and freshwater environments fostered the evolution of some fish into the first tetrapods—the family that evolved into all land vertebrates. These tetrapods first evolved into land animals before the end of this Period. Invertebrate land animals such as scorpions, spiders, and wingless insects also began to thrive in the new environments created by the vascular plant explosion.

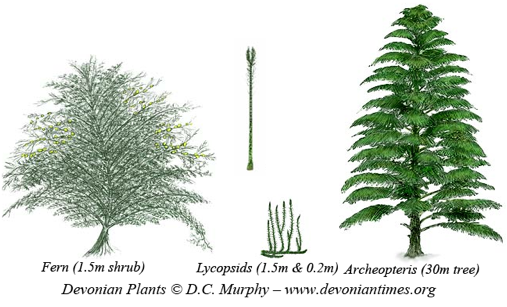

While the diversification of fishes is exciting, the Devonian vascular plant “explosion” is even more spectacular. Primitive Silurian-type plants (represented by Sawdonia in this display case) gave rise to the major vascular plant groups: lycophytes (clubmosses, spikemosses and quillworts) and euphylophytes (horsetails and ferns, and seed plants).

These plants transformed Earth’s environments, creating extensive marshlands. The new forests, dominated by the first trees, created a new biosphere and altered global carbon cycling. Complex soils were formed, land and water linkages were expanded, habitats became more complex and stable, and organic matter increased both on land and in the oceans though runoff.

The supercontinent of Gondwana dominated the southern hemisphere, while the smaller supercontinent of Euramerica was formed near the equator and the continent of Siberia lay to the north. Overall most of the modern continental plates were grouped together on one hemisphere of the Earth. The Euramerican and Gondwana plates began their collision that would lead to the eventual formation of Pangea. This resulted in great tectonic activity—some of which continued the formation of the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States and created the Caledonian Mountains in Europe.

Sea levels were exceptionally high during the Devonian, giving a widespread relatively warm and equable climate for most of the Period. A global cooling interval in the Mid-Devonian is associated with a drop in CO2 levels as plants covered the land, increased worldwide photosynthesis, and fixed carbon into both soil and sediments.

The Devonian Period ended with one of the five great mass extinctions of the Phanerozoic Era. However, unlike the four other great extinction events, the Devonian extinction appears to have been a prolonged crisis composed of multiple events over the last 20 million years of the Period. About 20% of all animal families and three-quarters of all animal species died out. Most extinctions were of shallow water and reef animals. Causes of the extinctions include global cooling, including glaciations in the south polar area of Gondwana, and anoxia (oxygen loss) in the oceans. Both effects resulted from indirect impacts of the new plant ecosystems—swamps and forests tied up carbon dioxide, while runoff into the seas provided carbon to be consumed by aerobic bacteria, depleting the oxygen needed by animals. Terrestrial ecosystems were largely unaffected by this extinction event.

* The Devonian was named for strata in Devon, England by Sedgewick and Murchison in 1839.

Devonian Animal (Metazoan) Fossils

Trilobites (ToL: Trilobites<Arthropoda<Ecdysozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Trilobites

Trilobites: Though declining in numbers, trilobites continued in importance and reached their greatest size during this Period. A number of small specimens are housed in this case:

Echinoderms (ToL: Echinodermata<Deuterostomia<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Brittle stars

Brittle stars (Ophiuroidea) are represented by a specimen on a rock slab.

Crinoids

Two Devonian crinoids (Crinoidea) represent these echinoderms: the delicate Bactrocrinus nanus and the basket-like Arthroacantha carpenteri.

Fish (ToL: Vertebrata<Chordata<Deuterostomia<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Placoderms

This extinct group of armored fish is represented by fossil skin from Coccosteus sp.

A cast of a medium sized Dunkleosteous skull hangs above the Devonian case. The live animal is portrayed in the museum life through time mura. This large placoderm reached lengths of up to 33 feet.

right view

right view![]() Dunkleosteous life reconstruction

Dunkleosteous life reconstruction

Mollusks (ToL: Mollusca<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Gastropods (Gastropoda).

Two snails are displayed: the slipper shaped Platyceras carinatum and Platyceras rarispinum. Both are replaced with pyrite.

Cephalopods

Cephalopods (Cephalopoda) are represented in this display by a pyrite replaced ammonoid, Tornoceras uniangulare. Some of the outer shell has broken away revealing the chambered structure. Manticoceras sp. shows some of the beautiful patterns cephalopod fossils are known for. Click on the cephalopod icon for the story of these animals.

Brachiopods (ToL: Brachiopoda<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Brachiopods

Brachiopods reached their widest diversity and greatest abundance during the Devonian. Some brachiopods are long and thin such as Mucrospirifer grabau, or the three specimens of Mucrospirifer prolificus.

Mucrospirifer prolificus, three specimens photographed from different views showing aspects of shell structure:

Paraspirifer bownockeri is more compact, but deeply grooved on one valve, with a corresponding ridge on the other.

Paraspirifer bownockeri grooved valve up;

Paraspirifer bownockeri grooved valve up;  Paraspirifer bownockeri ridged valve up;

Paraspirifer bownockeri ridged valve up;

Brachiopods or their shells were often used as a substrate by other organisms:

Aulopora microbuccinata specimen covered with a coral.

Aulopora microbuccinata specimen covered with a coral.

Mucrospirifer mucronatus brachiopod encrusted with bryozoans (see below).

Mucrospirifer mucronatus brachiopod encrusted with bryozoans (see below).

Orthospirifer cooperi: this specimen has another type of brachiopod, Phloihedron sp. growing on its shell.

Orthospirifer cooperi: this specimen has another type of brachiopod, Phloihedron sp. growing on its shell.

Another Philohedron sp. specimen shares its brachiopod substrate with some coral,

Two specimens are displayed to show some of the distinctive internal anatomy, including the coiled lophophore supporting structure of the brachiopod Paraspirifer bownockeri :

with partial shell removal as seen from:

click on the engraving to compare our specimens with known aspects of brachiopod anatomy.

click on the engraving to compare our specimens with known aspects of brachiopod anatomy.

Two specimens of Pseudoatrypa devoniana, shown from different viewpoints, are excellent examples of pyrite replacement,

Moss Animals (ToL: Bryozoa<Lophotrochozoa<Bilateria<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Bryozoans

Unknown bryozoans completely encrust the shell of a brachiopod, Mucrospirifer mucronatus. A fossil bryozoan, Sulcoretepora deissil, exhibiting pyrite replacement is prominant in our assemblage.

Unknown bryozoans encrusting a brachiopod shell

Unknown bryozoans encrusting a brachiopod shell

Corals (ToL: Cnidera<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Corals

Devonian colonial are represented here by Hexagonaria, a Petosky stone (Hexagonaria), a fragment of a tetracoral and by two specimens of the the tabulate coral Favosites turbinatus (end of cornucopia-shaped coral cut and polished to show inner structure), Favosites turbinatus, and another tabulate or chain coral, Halicites. Finally, the tabulate coral Aulopora microbuccinata covers a brachiopod shell.

![]() Hexagonaria cut slabe showing hexagonal units

Hexagonaria cut slabe showing hexagonal units

Hexagonaria Petosky stone

Hexagonaria Petosky stone

tetracoral fragment

tetracoral fragment

Favosites turbinatus tabulate coral chunk

Favosites turbinatus tabulate coral chunk

Favosites turbinatus cornucopia-shaped tabulate coral cut and polished to show inner structure

Favosites turbinatus cornucopia-shaped tabulate coral cut and polished to show inner structure

Halicites tabulate or chain coral

Halicites tabulate or chain coral

Aulopora microbuccinata tabulate coral covering a brachiopod shell

Aulopora microbuccinata tabulate coral covering a brachiopod shell

Solitary corals appear as the red horn coral Lophophyllum, the horn coral Heliophyllum sp., and as white shapes in a slab of black stone.

white shapes of cut horn corals against black stone. The arrows point to anatomical characteristics of these rugose corals distinguishing them from modern hexacorals.

white shapes of cut horn corals against black stone. The arrows point to anatomical characteristics of these rugose corals distinguishing them from modern hexacorals.

Sponges (ToL: Porifera<Metazoa<Eukaryota)

Sponges

Sponges: Two fragments of glass sponge (similar to the image in the icon above) are displayed.

Vascular Plants (ToL: Embryophytes [land plants] <Green Plants<Eukaryota)

On display are remains of an Early Devonian Tracheophyte. These plants did not have leaves, but did have trachea to transport water up the stems. They are among the earliest known vascular plants.

Details of the anatomy of this early plant are shown in the macrophotos:

![]() image showing spines (right edge of stem) and central tracheal element (center of stem, upper half)

image showing spines (right edge of stem) and central tracheal element (center of stem, upper half)

The engravings of Devonian fossils are from Dana, James D. (1870) Manual of Geolog; Le Conte, Joseph (1898) A Compend of Geology; Grabau, Amadeus (1901) Guide to the Geology and Paleontology of Niagra Falls; Shimer, Hervey (1914) An Introduction to the Study of Fossils, or Pirson, Louis and Charles Schuchert, A Text-Book of Geology. (1920).

©1998, Cal Poly Humboldt NHM | Last modified 29 October 2012

Basidechenella rowi

Basidechenella rowi Phacops rana milleri

Phacops rana milleri Trimerus vanuxemi

Trimerus vanuxemi Phacops sp

Phacops sp Furcaster

Furcaster  Bactrocrinus nanus

Bactrocrinus nanus Arthroacantha carpenteri

Arthroacantha carpenteri front view

front view Platyceras carinatum

Platyceras carinatum Tornoceras uniangulare

Tornoceras uniangulare Manticoceras sp

Manticoceras sp top

top edge

edge one valve removed

one valve removed the hinge

the hinge one end

one end top

top top

top Lophophyllum

Lophophyllum glass sponge

glass sponge